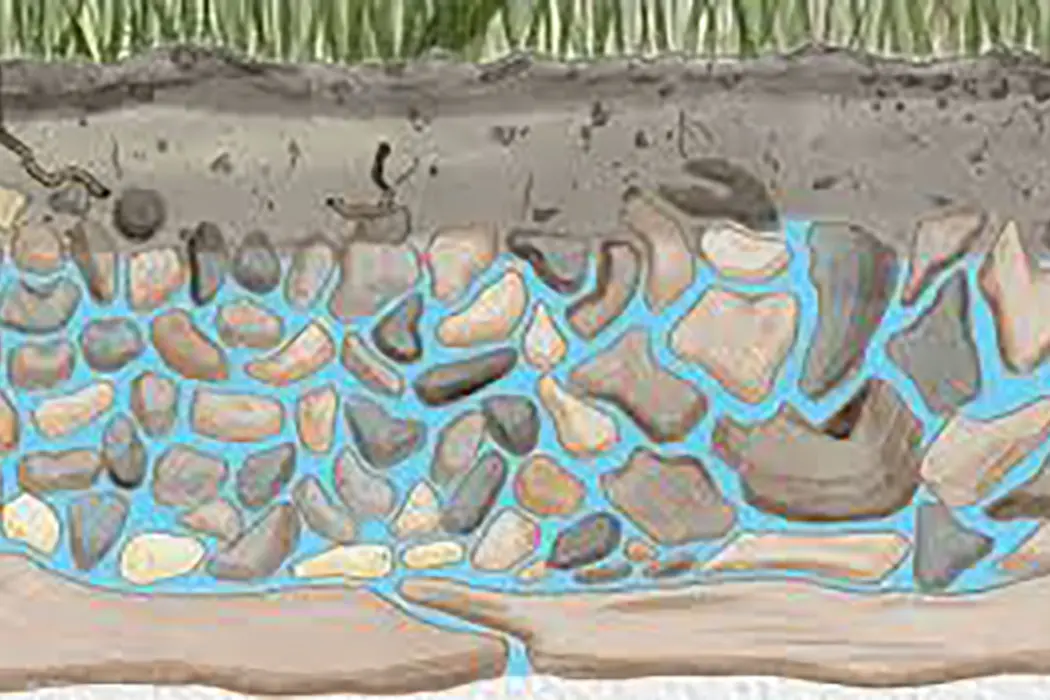

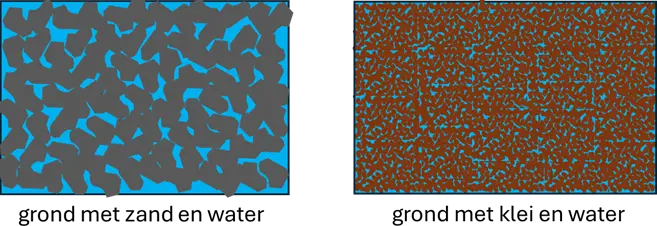

Groundwater is water in the ground. That water is in the spaces (the pores) between the sand or clay particles in the soil. Sand grains have a diameter of between approximately 0.1 and 1 mm. Clay particles are much smaller, even smaller than 0.001 mm. That is why the pores in a sandy soil are much larger than in a clay soil. Flowing water therefore has much less resistance in a sandy soil and can therefore flow much more easily than in a clay soil. Specialists then say that the permeability of a sandy soil is greater than that of a clay soil, and that a sandy soil is water-bearing and a clay soil is water-inhibiting.

Sand grains are solid and strong and behave like small balls. The space between the grains, the so-called pores, contains the water. The water content in a sandy soil is about 40%. Clay soil does not consist of solid particles, but of flakes (think of snow). There is a lot of water in those flakes. The water in a clay soil is therefore in the pores between the clay particles and in the flakes themselves. The water content in a clay soil can be as much as 90%. If you suck very hard, you extract water from those pores and from the flakes. The flakes shrink as a result. A clay soil can therefore shrink when you suck water from the soil, a sandy soil cannot.

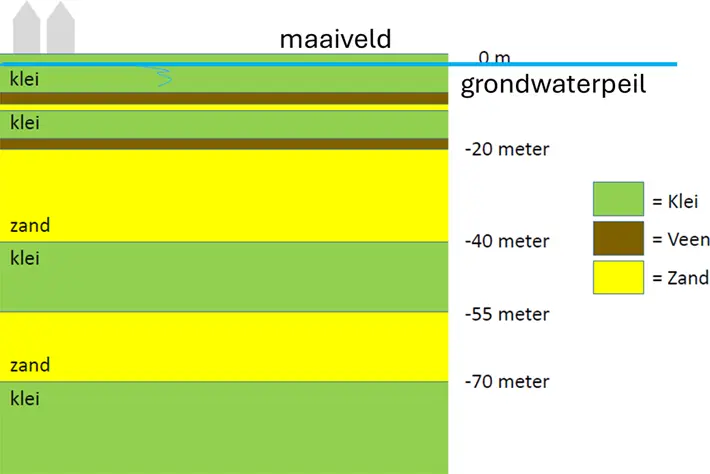

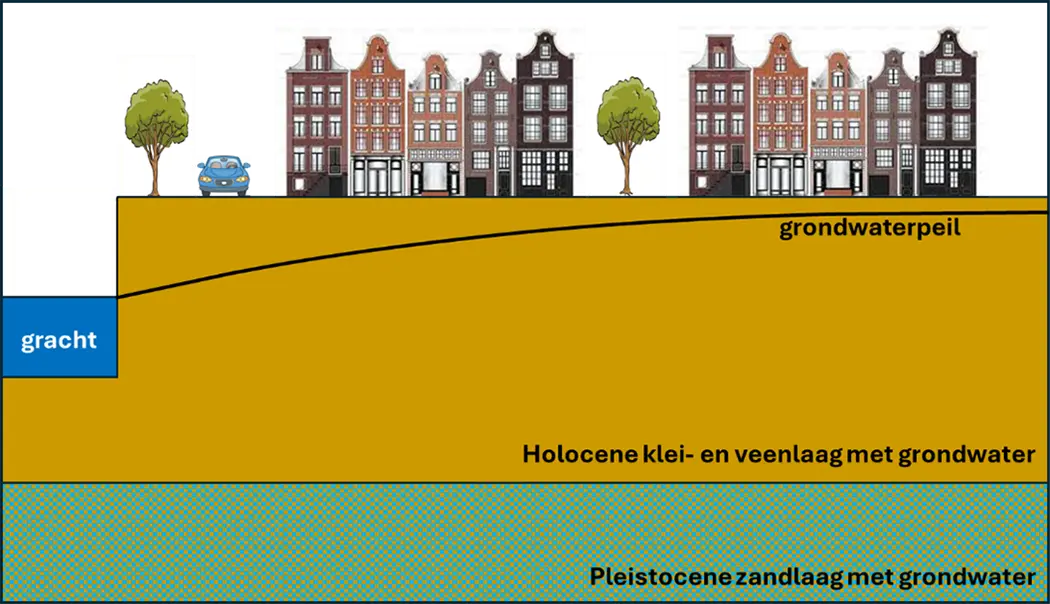

The top 20 meters of the soil in Delft and surroundings consists of layers of clay and peat. These are the so-called Holocene deposits, named after the geological period Holocene (until approximately 12,000 years ago, end of the last ice age). The permeability of peat is also very low. Below that we find a layer of sand approximately 20 m thick, so at approximately 20 below the surface. That is the so-called Pleistocene deposit (Pleistocene until approximately 2.5 million years ago). Below that lies clay and sand and clay, and finally at a very great depth we find rock. This is called the lithology of a soil, which is formed by geological processes.

Schematic structure of the soil in Delft.

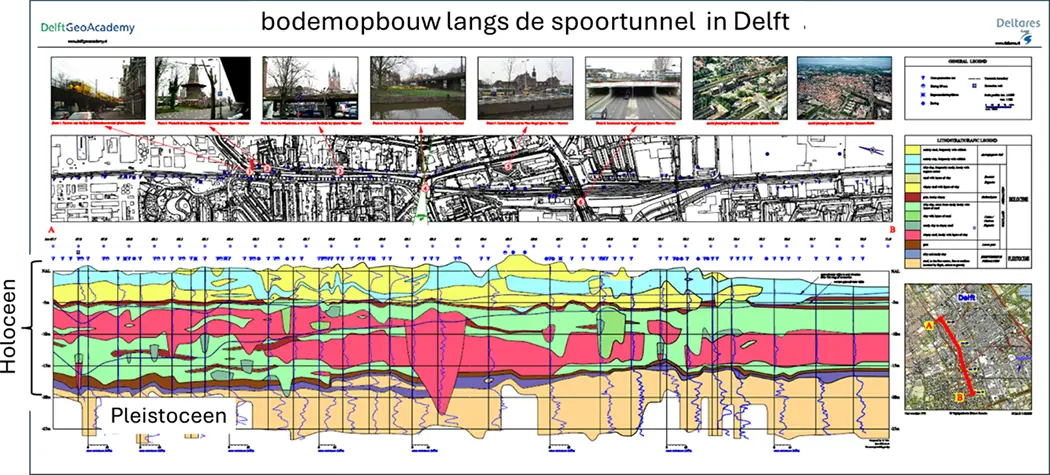

In reality, the soil structure is not so beautifully layered, but much more irregular. This makes the regulation (management) of groundwater in the city a lot more difficult.

Actual structure of the soil in Delft along the railway tunnel route with the approximately 20 m thick clay and peat layer from the Holocene on top and the 20 m thick Pleistocene sand layer below.

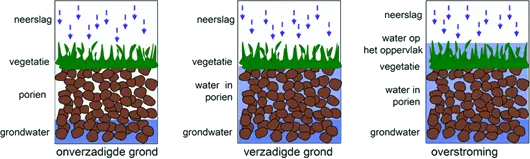

Anyone who has ever dug in their garden or on the beach knows that you only come across water after a while. That is also the case in the city. The water is at a greater depth, in Delft several decimetres deep. That is the groundwater level – some also call it the groundwater table. That level can vary if it rains a lot, or if it remains dry for a long time. That variation occurs more quickly in sandy soil than in clay soil because of the larger pores (greater permeability).

Water in the soil when it rains.

The water level in the Delft canals is determined by the water level in the Rijn-Schiekanaal, which is regulated by the Hoogheemraadschap van Delfland. They aim for a level of 43 cm below NAP (Normal Amsterdam Level), even if it rains a lot or a little. We call this the bosom level. If it rains a lot, the groundwater level rises above the water level in the canals. Because water flows from high to low, including groundwater, the high groundwater slowly flows into the canals. This creates a convex groundwater level. The opposite happens if it is dry for a long time. The groundwater level then drops, partly because trees and plants absorb a lot of water from the ground. Then water flows from the canal to the solid ground and a concave groundwater level is created. But the latter does not often occur in Delft.

The groundwater level in Delft in relation to the canals. The groundwater flows slowly from high to the lower canal (drawing not to scale).

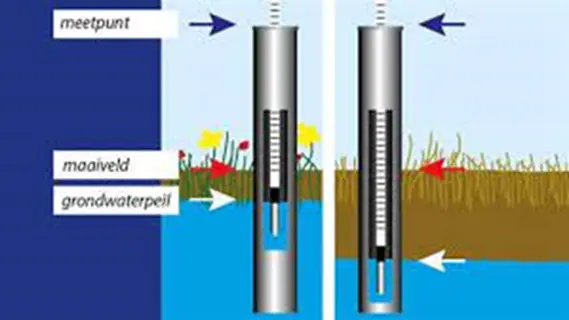

Because the top 20 m of the soil in Delft consists of clay, the groundwater flows very slowly to or from the canals. The groundwater level in Delft can therefore become very high when it rains a lot. Then there is little room for water storage in the ground: rainwater has difficulty entering the soil. This can cause a lot of inconvenience, which is why the Municipality of Delft and the Delfland Water Board measure the groundwater level in so many places. In the past, this was done by hand, but nowadays with floats whose height is read electronically and whose data is collected centrally. Because 210 of these wells have been installed, everyone can read the groundwater level near their home.

Level tube with float to measure the groundwater level.

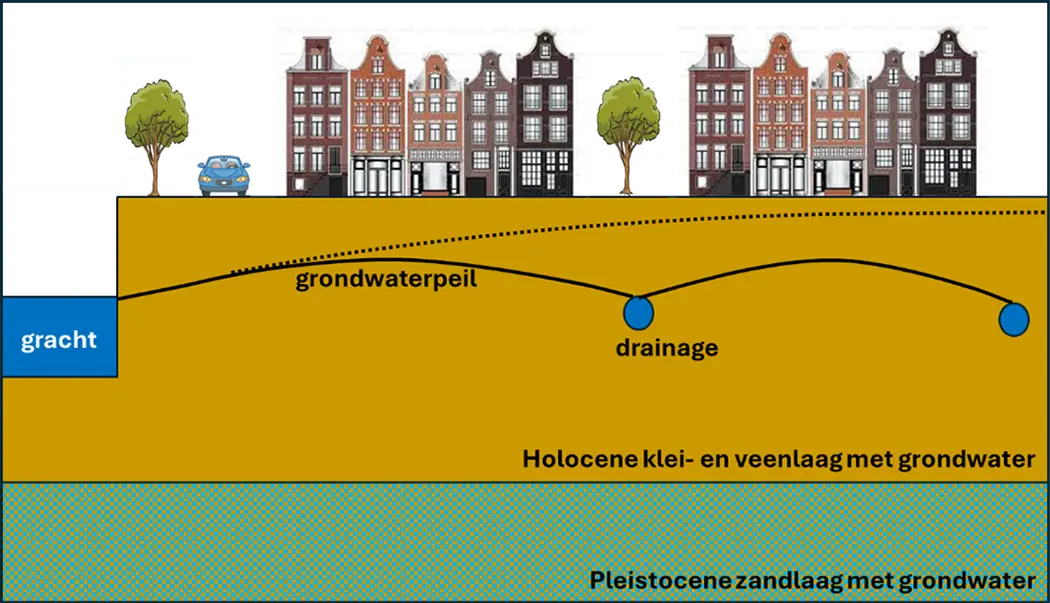

Fortunately, there are methods to lower the groundwater level if the high water causes too much inconvenience. You do this by laying a porous pipe in the ground, below the groundwater level that is causing inconvenience. You then connect that pipe to the surface water. The surrounding groundwater then flows to that pipe and is drained away. The groundwater level drops. The closer the pipes are to each other, the lower the groundwater level.

This is called drainage, and the Municipality of Delft uses it to compensate for the effects of fluctuating groundwater levels over the year and the possible effects of, among other things, the railway tunnel and the reduction of groundwater extraction by DSM.

Lowering of the groundwater level in Delft by drainage (drawing not to scale; dotted line indicates groundwater level without drainage).