The Netherlands was of course always wet. Rain, grey weather with little evaporation in a low-lying country with polders and large rivers. Traditional thinking in the Netherlands was that there was always enough, and often too much water. Water was considered a potential problem and rainwater needed to be drained away as quickly as possible. So we kept the water outside with high dikes. Or it was quickly drained away through our many canals and ditches. And later via our sewers. The first were so-called mixed sewers. They also drain waste water from toilets, kitchens, companies, etc. All the rainwater that enters the sewer via the drains along the road was therefore mixed with that dirty water.

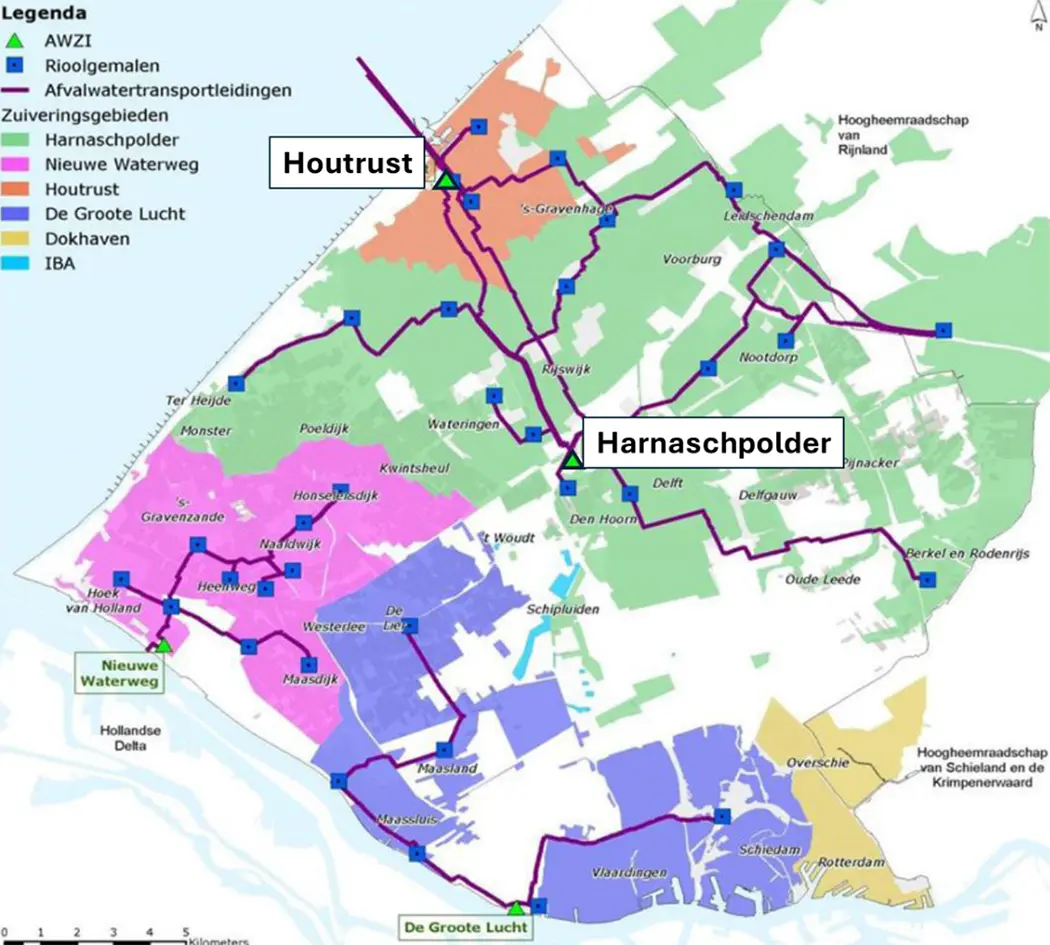

These sewers come together in the main sewer network, which takes the wastewater to a water treatment plant. For Delft, this is the Harnaschpolder Wastewater Treatment Plant, where wastewater from other municipalities in the area is also treated. The treated water is then discharged into the North Sea at Scheveningen (Houtrust). But part of that water, the rainwater, was clean and did not need to be treated at all. A waste of all the effort and money.

Our old sewer system was designed to be able to discharge precipitation of up to 20 mm per hour. A precipitation of 30 mm per hour can no longer be processed by such a combined sewer, and the excess is discharged into the surface water via one or more of the many overflows of the Delft sewer system. This of course has negative consequences for the quality of that surface water. That is why Delft has started to separate the discharge of precipitation and waste water. This separation is not yet complete and is not possible everywhere, for example if there is too little space in the street. Delft currently has 120 km of combined sewer, and a separate system with 113 km of waste water sewer and 140 km of rainwater sewer. This concerns the so-called main sewer, so excluding all connections to homes, businesses, etc.

Of course, it is very expensive to build and maintain such a double sewer system. Moreover, in the future, much more water would have to be drained during heavy rain showers. Because due to climate change, not only the total precipitation is increasing, but also the peak precipitation during heavy showers. For example, the once-in-100-year peak precipitation is expected to increase from 58 mm per hour in 2020 to 70 mm per hour in 2050.

Delft’s sewage system is connected to a large main sewer network, the wastewater of which is cleaned at the Harnaschpolder Wastewater Treatment Plant before being discharged into the North Sea.

We take it for granted that Delft has a sewer system. But in the past we didn’t have that and all waste water was discharged into the canals. In the course of the 19th century this became an untenable situation. So plans were made, but everything took a very long time. For example, in 1866 a report was published with the recommendation to fill in the Delft canals and to construct closed sewer pipes. Fortunately, that didn’t happen. After that it took about another 60 years before the municipality started making serious plans for a sewer system. It wasn’t until 1928 that those plans were approved and work began. Incidentally, the construction of our sewer system was only completely completed in 1953. Such a system has an average lifespan of about 60 to 80 years. So for some time now Delft has had to replace many sewer systems. You’ve probably noticed that yourself.